I have been working with a team of 5th-grade teachers in Kentucky whose goal is to help students become self-directed learners. One of the teachers could retire, but she is having so much fun seeing her students grow, that she is continuing to teach. This team checks all of the boxes for a model Professional Learning Community (PLC) including goal setting, analyzing student data, sharing ideas, implementing action plans, and monitoring progress. However, their success is not attributed to PLC structures and protocols, but rather their willingness and desire to learn and grow as educators.

PLCs as Avenues for Adult Learning

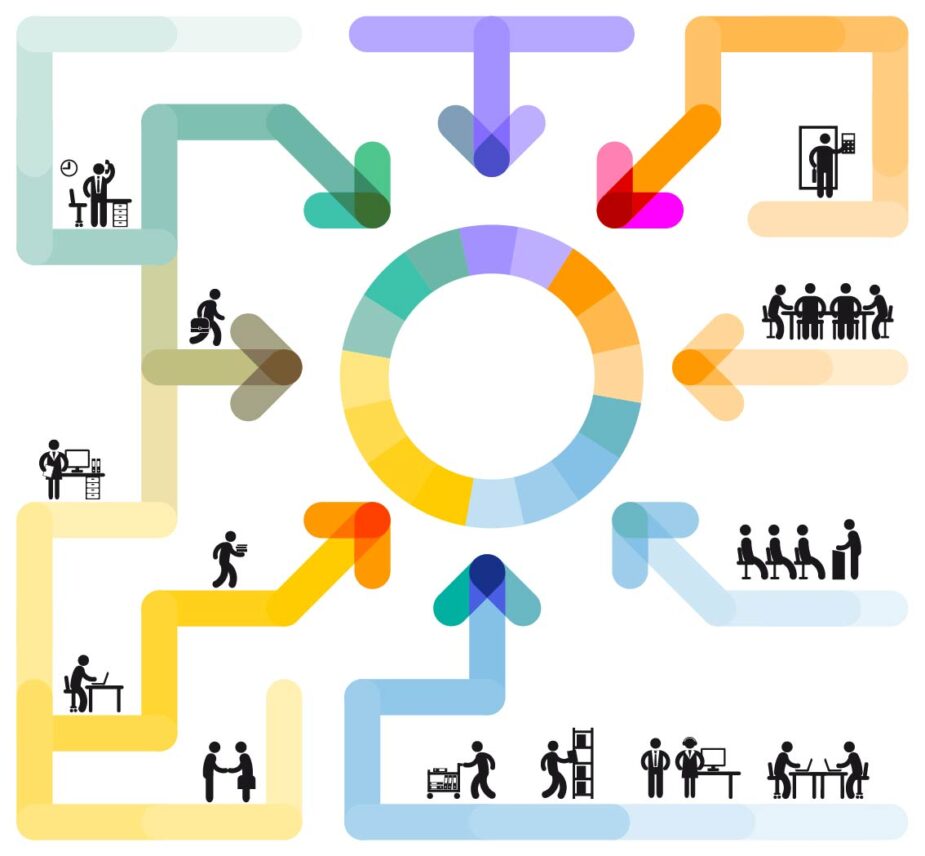

PLCs and collaborative data discussions are being implemented in school systems across the continent. I’ve observed teachers having on-task data conversations that feel productive. Teachers follow a PLC or data protocol, talk about student scores, and make a plan for how to respond. The efforts of PLCs are observable in many school districts, but research suggests that evidence of their effectiveness is lacking. How do we leverage PLCs to generate enthusiasm for teaching and impact student success like the 5th-grade team I described? We use an abundance of student learning data as fuel to drive educators’ learning, leading to action, and ultimately celebrations of student growth.

The protocols and norms that schools have established for PLCs and data conversations are the foundation where adult learning can occur. A common vision for PLCs is that teachers would learn from student data and each other about effective teaching strategies. They are called Professional Learning Communities after all. In the case of the 5th-grade team, further learning takes place when teachers practice a new strategy and gain insights from the teaching experience in real time. They are constantly learning, applying, reflecting, and looking at student data to determine whether a lesson was a success or not. Likely your PLC structure and protocols are good. However, if the structure isn’t leading to the type of adult learning described here, a few shifts in the adult learning culture can ignite teacher learning in exciting new ways.

Ground Statements in Evidence

Ground statements in evidence is a common PLC norm. You might have it, or something like it, as a foundational norm in your PLCs. The reason this norm is so important is that without it, conversations tend toward making assumptions and generalizations and shifting responsibility. Analyzing data requires the posture of a learner who is looking to gain new insights by turning data into usable information. Unfortunately, our current education climate is one of evaluation and fear rather than curiosity and inquiry. Adult learning will not occur when teachers are afraid of what the data says about them. Assumptions and generalizations occur when school systems focus on accountability over improvement, or teachers are simply working hard and don’t want to see that their efforts aren’t reflected in student scores. Take a look at the examples below. Do you see any of these tensions happening in your data conversations?

Assumptions

Examples of assumptions about student data include:

- “I know which students will struggle.”

- “I know what the data are going to say. I teach all of the _______ students.”

- “I already know which topics students will struggle with.”

It is hard to learn from data when we walk into a conversation with preconceived ideas about what the data will say. Curiosity about student data allows us to be surprised by what we think we know. We don’t want to downplay the deep knowledge a teacher gains about their students through classroom observation, formative assessments, and daily interactions. However, the power of a data protocol is to transform data into actionable information. To do so, we need to use actual evidence, not what we think is going on with a student. If we assume a student will score low, we miss the opportunity to celebrate their strengths. If we assume a student will do well, we might miss a standard that they are struggling with. I’ve observed that when a teacher moves past an assumption to look hard at the evidence, they can’t help but spring into action in response to what a student needs.

Generalizations

Like assumptions, generalizations about a group of students prevent educators from learning valuable information through a data conversation. The following statements limit understanding because they generalize data rather than explore evidence about each student:

- “Students were ‘checked out.’”

- “None of my students understand _____.”

- “All of my students did great.”

By making a blanket statement about everyone, we miss the opportunity to gain new insights about student comprehension. I remember as a math teacher feeling very defeated by test scores. I complained that “All of my students failed.” One time my department chair asked me specifically “How many students failed? Who are they? What didn’t they understand?” I was taking it personally that students were missing questions that I had emphasized daily throughout the unit. This mindset didn’t allow me to understand learner needs at the individual level. By getting specific, I was able to remove my feelings about student performance and understand who needed additional support. What felt like all students were actually only five students. Once I got past the generalization, I was able to reflect on my teaching and consider different approaches that would serve my students better.

One teacher I worked with in New York expressed a sentiment held by many educators saying “I used to think data gave us limited information.” This teacher, and others who feel the same way, are not wrong. When data conversations circle assumptions and generalizations the data is limited. They went on to say “…now I know there are many questions we can use to dig deeper, so I will use data to help improve outcomes for both teachers and students.” Being a learner of student data includes collecting a variety of high-quality data sources, knowing the purpose of different types of data, interpreting the data, and understanding the root causes of what the data are saying. An adult learning culture invites teachers to ask questions and explore what additional data sources would serve their learning needs. When we expect teachers to have all of the answers before, during, and after a data conversation, we inadvertently dissuade a learning posture, which is the whole point of PLCs.

Shifting Responsibility

A third group of statements that stunt teachers’ learning from data comes in the form of shifting responsibility. The following statements are examples of making someone or something else responsible for what the data might say:

- “This student needs a tier 2 or tier 3 intervention.”

- “That was a bad question.”

- “I don’t think the data set is right/complete.”

- “This is a ‘home’ issue, not an instruction issue.”

While these statements may have some truth, they block an opportunity to have a tier 1 instructional impact on student learning. We can still create tier 1 responses to student data, even if a student is receiving additional support. We can still learn something about students from a lousy question. A teacher in NY realized that “It’s ok to have ‘hard’ conversations surrounding data, but avoiding the data will not benefit students.” To take responsibility during a data conversation is hard and vulnerable. Another teacher said, “I used to think more about changing the data than considering what is going on with the student.” The disconnect between the purposes and outcomes of a data conversation leads to unhelpful practices around data discussions. Shifting the PLC focus from having answers to gaining insights, helps teachers open up to the possibility of learning. This breaks down some of the natural defensive responses such as assumptions, generalizations, and shifting responsibility.

The Root of Fear-Based Data Conversations

Let me be clear, assumptions, generalizations, and a shift of responsibility are all fear-based responses to data conversations and are not the fault of teachers. There are valid reasons for teachers to be afraid of sharing their student data and diving into a conversation. One reason is the confusion between data for accountability and data for improvement. While an administrator might communicate and believe that PLC conversations are for improvement over accountability, that might not be the perception of teachers. A teacher might have transferred from a different district that emphasized accountability. Or, teachers might be internalizing the culture of accountability that is pervasive across the country. It is also a mixed message to have student growth as an accountability measure on the teacher evaluation, and to say “This PLC conversation is for student improvement.” While we might not have control of the accountability pieces of student data, awareness of teachers’ internalized stress will help us move past the barrier to create conditions for adult learning.

Teachers work hard to help their students learn. Some don’t want to engage in a protocol that might reveal that their efforts aren’t working. To help address fears about what data will say about them and their teaching, we have to help teachers understand what the data mean. It is vulnerable to share student data with colleagues. Fearing comparison and judgment is a common feeling for teachers. It is easier to make statements of assumption, generalization, or blame rather than facing the fear of what the data will say. In addition, for some, data is tied to math anxiety. Teachers might be hesitant to engage in dialog because they are afraid they won’t understand the quantitative data. One teacher I worked with said, “I used to get overwhelmed by data, but now I want to be a learning scientist.” To set the conditions for rich data conversations that get past the barriers of teachers’ fears, we have to help them see and experience information from data as helpful to their role.

Creating a Culture of Adult Learning

Data is not a judgment or evaluation. Data is not a decision. Data is information. That information can be used to show teachers opportunities for improvement or change in their instruction. Information is actionable. Knowledge is power. When teachers are equipped with an understanding of their students, they are motivated to learn and apply new teaching strategies in their classrooms.

The 5th-grade team in KY operated in a traditional, surface-level way until recently. They had on-task meetings and were generally productive. When they decided that they wanted to do the challenging work of growing self-directed students, their collaboration shifted from generic conversations that included assumptions and generalizations and became much richer. They will admit that they didn’t think their students were capable of as much independence as they are exhibiting now. These teachers became curious. They started learning new strategies to try with their students. They began collecting more formative assessments and looking at trends in the data. They were willing to be surprised by the data. By helping students become self-directed learners, they saw improved test scores. This happened because they were willing to learn and change their teaching. When they started to see some success through student data and behavior, they were motivated to learn more. This has led these teachers to experience the most fulfilling time of their careers. Both they and their students are benefiting from their professional growth.

In working with educators in New York and Virginia on developing their data literacy skills, I’ve witnessed educators shift from being defensive and afraid of data to being excited for what they will learn about their students. One teacher reflected, “I think we need to question our assumptions as much as we question/lean into the data.” The professional learning experience helped this teacher and others see where their data conversations were falling short. The next iteration of this journey is to go deeper into the data to understand how to apply their learning to effective teaching strategies that are responsive to students’ needs. This produces a powerful learning cycle of teachers learning from data, applying an effective strategy, and witnessing student success. Once teachers have experienced a fruitful cycle of collaborative learning, they are empowered to dig deeper and learn from all the data available to them.

Advanced Learning Partnerships’ service, Learning Data, leads educators beyond common pitfalls of data conversations and amplifies the conditions for adult learning that create an environment for the effective use of student data. We work with groups of educators having collaborative data conversations to learn about and practice the five data literacy skills that lead to student impact. Learn more about data literacy for educators and how to cultivate an environment conducive to learning from data and classroom instruction.